Edith Farnsworth House Was A Beautiful Disaster

For better or for worse, Edith Farnsworth House is one of the most important architectural landmarks constructed in the 20th century. It was an uncompromised vision of its architect and spawned countless imitations. The minimalist aesthetic came at a heavy cost. Originally designed as a weekend escape tucked away from prying eyes, the home went well over budget, had countless engineering compromises, and turned client and architect against each other. Edith Farnsworth House sent shockwaves throughout the architectural community upon its completion and it’s still reeling from it nearly 70 years later.

FINE AND INTERESTING

To you, this parcel of land in Plano, Illinois is scenic, if a bit unremarkable. To Dr. Edith Farnsworth, it was a blank canvas. She bought the 9-acre plot from Robert. R. McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, for $500 an acre with possibilities rushing through her mind. She worked as a nephrologist in the city and wanted to build a weekend getaway where she could escape from the stresses of her job. Buying the land was just the first step toward this.

Next, she focused her attention on finding someone that could design the thing. George Fred Keck was a local architect that had dipped his toes in the modernist world. Perhaps his best-known project was the House of Tomorrow, which was first unveiled at the 1933 World’s Fair. Trademarks of his style could be seen in its straight edges as well as the extensive use of glass and outdoor elements throughout.

He probably would have given Farnsworth’s home a similar treatment, but the deal fell through. Keck only would have done it if he were given free rein to do as he wanted. Farnsworth wasn’t one to sit on the sidelines. And why should she? The weekend house would have to be put on hold for the moment. Farnsworth changed her mind and set the project on the back burner for a bit.

Things would get kicked back into gear in 1945. She met another architect at a dinner party: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. She knew he was a prominent figure in the field, but couldn’t tie any buildings to him. Outside of a few architectural circles, he was a relative unknown in the United States. He spent most of his career making a name for himself in Europe. His work before the Second World War included the Barcelona Pavilion and the Villa Tugendhat, which were completed in 1929 and 1930, respectively. These were watershed moments in the modernist movement and actually predated Keck’s World’s Fair home by several years. Mies could have continued to add to his portfolio, but deteriorating conditions in his native Germany forced him to immigrate to the United States in 1938. He spent much of his time in the country working in the architecture department at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Farnsworth thought that he was more than capable of handling the project. She told him that she wanted to spend between $8-10,000 on her weekend home. This isn’t an insignificant sum. It would translate to nearly $165,000 in today’s money. For her, it was a small price to pay for her home away from home. Mies ran an office in Chicago and she probably didn’t want the man to worry himself over a relatively small project. She asked if there was someone at his firm that could spare the time to work on it.

The two of them must’ve really hit it off during the party because Mies said he’d do it himself, on one condition. Recalling the conversation many years on, he said:

“When we talked the first time about the house, at that dinner party, I told her that I would not be interested in a normal house, but if it could be fine and interesting, then I would do it.”

And just like that, they had a deal.

PLANNING PHASE

The two of them spent 1946 and 1947 going to the site and planning their course of attack. Mies thought the plot was beautiful, though it presented them with a unique problem if you could even call it that. Architects will usually find the best view on the lot and then try to find ways to design the structure around it. The “issue” was that every view on the plot was sublime. He couldn’t emphasize just one. This intertwined with another unique aspect of the acreage. It was shielded very well from prying eyes. Forestry to the north obstructed the view from River Road and the nearest bridge was a half-mile to the west. A large sugar maple tree would also obscure the house from those on the river to the south.

He had previously discussed making the home out of stone or brick, materials that he’d become innately familiar with during his formative years working in the family business. That simply wouldn’t suffice here. During one of their trips to the building site, Mies brought up the idea of making it out of glass. He wanted to bring the outside world into the interior of the structure and ensure that none of the views went to waste.

This decision complicated other aspects of the structure. Thermal issues would have made the summer and winter months that much more brutal. Air conditioning systems hadn’t yet been widely adopted in homes. Farnsworth wasn’t going to be using it every day, but its livability still would’ve been compromised. The structure’s placement became less about making the most of the breathtaking sights and more about mitigating the sun’s wrath.

Mies detailed the “passive solar design” with the following quote:

“We placed the house very carefully underneath the trees to cover it as much as possible against the sun. I observed the angle of the shadow at many hours, and we moved the house so close to the trees that we kept the sun as much as possible out in the summer and we would like the sun in the winter.”

There was another, more concerning weather-related issue. The desired build site was a mere 75 feet from the Fox River. It was known to overflow from time to time. They didn’t have to build the house there. remember, they had nine acres of land at their disposal. Farnsworth suggested placing it further up the slope and out of the floodplain, but Mies was determined to make it work in the space that they’d picked out.

He did some digging to find out the history of flooding in the area. He would use this information to design some sort of safeguard against it. The Illinois State Water Survey didn’t keep such records on hand. They suggested that he interview the locals on the matter. They’d know more about this than anyone else. The testimonials weren’t very encouraging. Many of them stated that they’d seen that piece of land underwater. Did any of this do anything to change his mind? Of course not. Mies was set on making it work. We’ll cover how they tried to work around this a bit later.

The excursions to the Plano site were plentiful, but construction wouldn’t commence for another two years or so. Pretty much the only work done on the house was a watercolor sketch and a handful of plywood models. Mies’s office was swamped with work and the house was set on the back burner.

Money was also a major pain point. The $10,000 mark that was thrown out at the dinner party was unrealistic for what they were planning. Farnsworth felt that she needed to make a stronger financial commitment to the project if the house had any hope of getting built. She paid Mies a visit at his apartment and put up $40,000 for the cottage.

While this showed that she was serious about getting the project off of the ground, it still wouldn’t be enough to actually build it. At some point after the apartment visit, Mies even told her outright that it couldn’t have been done for that price. She had about $65,000 in assets but obviously didn’t want to spend it all on the house. It was stuck in limbo until May 1949. Farnsworth received an inheritance of $18,000. This was the spark needed to finally move forward with the weekend home.

Cost projections were detailed even further in June. Mies tasked Myron Goldsmith, one of his employees, with creating models of the house in three different sizes and costs. 84x30x10 at $69,250; 77x28x9 at $59,980; and 77x28x10. They split the difference between the latter two proposals and decided on a 77x28x9.5 plan. Mies wanted to keep costs at around $60,000. Philip Johnson’s Glass House was made for around this price and he thought that was an appropriate figure for their own project. A full four years after that fateful dinner party, Work would finally begin on the riverside abode.

CONSTRUCTION

If there's one thing you should know about Mies van der Rohe, it's that he's VERY particular. This was best illustrated when a potential contractor came up to Plano to grade the site. Mies wanted a grade that was within a tenth of an inch. If you aren't familiar with this kind of work, just know that this is a ludicrously precise measurement. The contractor couldn't believe what he was hearing. The situation only escalated from there and ended with the man telling Mies to, uh, go south for the Winter. Many contractors didn't want to touch the project because of its unusual nature, and those that felt like they were up to the challenge were scared off by the architect. With no one else willing to take on the job, he had no choice but to take on the role of the general contractor.

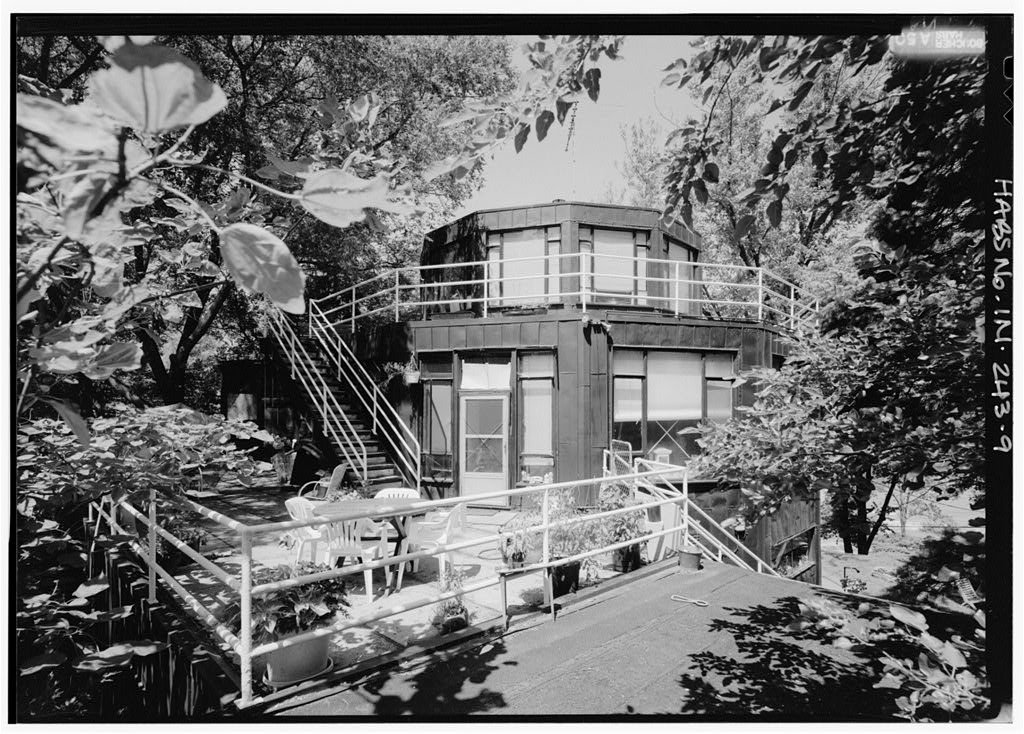

Construction officially commenced in May of 1949. Let’s start with the biggest hurdle in their way. To get around the potential of flooding, they decided to place the house five feet three inches off of the ground. This was about two feet higher than the flood heights that the locals gave him. The minimalist execution fit in with everything else about the house.

The columns and steel girders were made by Wendnagel Steel Company. This wasn’t the first time they worked with Mies. They knew how demanding he could be. He wanted strict 1/16-of-an-inch tolerances. The girders were measured, assembled, bolted, and disassembled before being shipped to the site. Additionally, Goldsmith made a 6-foot-long mercury level to ensure that the lines and corners were correct.

Wendnagel sandblasted, rustproofed, and painted the steel columns. They’re attached to the structure by plug welds. Michael Cadwell, a professor at Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture, detailed the process in his paper Flooded at the Farnsworth House. He says:

“Steel erectors first drill the columns and beams and join them with bolts; they then level and square the frame and secure the nuts; next, they loosen and remove these same bolted connections one at a time and weld the now vacant holes solid (plug); and, finally, finishers sand the welds smooth.”

There isn’t any apparent evidence of welding. The support beams appear to effortlessly lift the structure off of the ground. It complements the home’s clean lines and is vital to establishing the minimalist motif.

The glass was another integral part of the house. The Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company brought massive panels to the building site and cut them down to size on the spot. The quarter-inch-thick windows were originally meant for storefronts. In their intended environment, they’d showcase merchandise and lure in passersby. In this context, they’d call nature into the interior. Interestingly, Mies decided against using double-pane glass. It cost several times as much as standard glass sheets and wasn’t as widely available.

The aesthetics were in order, but more critical aspects of the structure still needed to be sorted out. Elevating the home off of the ground meant that they couldn’t install the utilities in a conventional way. A 4-foot cylindrical tube or “stack” brought in electricity, heating oil, and water and expelled waste. The power lines were also placed underground. This preserved the house’s exterior lines, but this also increased construction costs. Farnsworth refused to have a driveway put in. Although it would have made accessing the house easier, it also would have compromised its privacy. The road would have spanned from the county highway on the northern border of the property all the way to the house.

The flooring was one of the most contentious issues of the construction process. Limestone, concrete, tile, and bluestone were considered, but Mies insisted on using travertine. This is a type of stone that forms in mineral spring deposits. He was innately familiar with the material. It was used extensively in the Barcelona Pavilion. After work on this project concluded, he would go on to incorporate it into works such as the Seagram Building and 860/880 Lake Shore Drive. Heck, he even used it in his own Berlin apartment.

There was just one problem: travertine was incredibly expensive. Alex Beam, the author of Broken Glass, says that the cost of the material for this project was between $12,000-13,000. Mies knew of its extravagant price and initially tried to see if his brother could supply it for them at a reasonable price. This deal fell through, so he had to source it from a quarry in Carthage, Missouri. This came with its own set of complications. Ice could expand in its pores and cause damage. To combat this, Mies designed a drainage system that resembled a shower pan. The terrace was even tilted at a slight angle toward the river to keep water from sitting on the property. They also installed an inlaid radiant heating system, which cost an additional $850.

Mies and Farnsworth clashed on the finer details. Take the curtains, for instance. Mies wanted to leave them out entirely and only included them at the insistence of Dr. Farnsworth. He wanted to use silk shantung curtains that would have given her privacy without meddling with the pristine views outside. The entire point of building in that particular spot was to take full advantage of the good views all around. To him, it would’ve been foolish to use any other material.

Dr. Farmsworth sought the opinion of Chicago architect Harry Weese. He said that brown curtains would compliment the outdoor palette during Autumn. Somehow, it all got back to Mies, who wasn’t too happy about the second-guessing.

PROS AND CONS

It was definitely a stressful build process, but the end result was truly an architectural marvel. Visitors approach the house from the south. Many elements on the exterior emphasize its orthogonal lines. Verticality dominates in the lower terrace and main level. The two staircases play into this as well. They lack railings and are essentially slabs of stone. These are somewhat countered by the horizontal supports. All of this is in stark contrast to the natural organic shapes that surround it.

The interior is one large room that measures 55x28 feet. This echoes the flow from the outdoors and contributes to the merging of the two environments. Even still, Mies managed to section off the inside. He uses the large rectangular service core to his advantage. When visitors enter the house they’ll find themselves in between two sectors. To the right is a work area and to the left is a dining space. The home makes use of Mies-designed furniture, but it wasn’t always this way. He sent a shipment of furnishings to the home back when it was being worked on. Dr. Farnsworth refused to accept it. She opted to use pieces of her own from other designers. It wasn’t until after it left her ownership that the Mies's furnishings were put in place.

Let’s continue down the right side of the house. Here, we find ourselves in a kitchen with some rather unusual proportions. Countertops and cabinets are arranged in thin strips alongside the service core. At the far end of the house is the sleeping area. A living space complete with ottomans, leather chairs, a lounger, and a fireplace is right around the corner. Finally, the house has two bathrooms stowed away at the front and rear of the service core. The guest bathroom has a standing shower while the master bathroom has a tub.

Edith Farnsworth House is a staple of modernist architecture, but as a space to be lived in, it leaves a bit to be desired. The use of glass is integral to bringing the outside in, but it also made the home scorchingly hot in the summer and unbearably cold during the winter. An air conditioning system wasn’t installed. Granted, the technology hadn’t yet been widely adopted in the 40s and 50s, but if any house could’ve used it, it was this one. Instead, it had to make do with a combination of boilers and fans.

There was also a set of small hopper windows at the east end of the house. This system was wholly inadequate for controlling the house’s temperature. It also didn’t help that it was poorly ventilated. This contributed to its inability to withstand the elements and made using the fireplace a chore. The mere act of smoke going up the chimney could cause a negative interior pressure. The house would pull air into the house through the chimney, sending smoke back into the home’s interior.

These thermal issues were reflected in her outrageous heating bills. Her heating bills from the fall of 1951 to the spring of 1952 total $668 dollars, which would translate to over $7,500 in today’s money.

There was little privacy despite its relatively isolated location. Architects and students would visit the site during and a bit after the construction phase, often at the invitation of Mies. And they just never stopped coming. It seemed like everyone in the architectural world wanted to lay eyes on the newest Miesian masterwork. The seclusion that they worked so hard for was for naught. She could at least take solace in the fact that the home hadn’t gotten washed away by the Fox River… yet.

The most stressful issue for both Mies and Dr. Farnsworth was money. Building costs had far exceeded even their most pessimistic estimations. The Korean War had jacked up the price of essential materials such as steel and concrete. It also took up a large portion of their time. What began as a side project for Mies turned into something that he and his associates couldn’t escape from. Billable hours had swelled to just under 5,900.

On August 1, 1950, the firm informed her that they’d spent $69,868.80 on the home. Up to this point, she spent about $69,000. A week after receiving the letter, she wrote back to them saying that she wouldn’t dedicate anything past the figure listed in the statement. Although she did continue to pour money into the house, this did show that she was getting fed up with the whole thing. Worse still, they had yet to factor in the fees for Mies’s architectural and general contracting services. According to Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography by Franz Schulze and Edward Windhorst, not listing professional fees was consistent with his past practice. Still, it’s crazy to think that compensation in this regard hadn’t come up in the five years they’d spent working together.

Later on, she did send the office checks for $1,000 and $2,500. She classed the former as a “voluntary contribution.” The latter, meanwhile, was to “go toward a fee of which I suspect Mies stands in need.” These wouldn’t have come close to covering those other expenses.

In spite of the never-ending delays, unconventional design solutions, agonizing perfectionism, and conversations about migration patterns, the house had gotten to a state where Edith could at least spend a night there. She paid the Plano estate a visit on New Year’s Eve 1950. Although work on the home continued into March, she was at least able to finally enjoy her home away from home.

COURT CASE

Mies and Dr. Farnsworth had stopped talking to each other after their communications in August of 1950. The construction process had strained their relationship beyond repair. And with the house en route to completion, they had little reason to keep in contact with one another. Much to their dismay, their business wasn’t finished quite yet.

The catalyst that reignited the feud was unassuming enough. Mies complained to fellow architect Philip Johnson about his offices’ financial struggles. Johnson recommended Robert Wiley, a business consultant and real estate development partner of his, to see if anything could be done.

Wiley scoured the books and found a $4,500 balance due for construction costs on a project. He suggested that Mies try and collect the money. He thought he discovered the root of their issues, but he actually stepped on a land mine. This was the amount owed on Farnsworth House. Wiley got in touch with Dr. Farnsworth’s attorney Randolph Bohrer but couldn’t come to an agreement. He then convinced Mies to meet him in person. Here, the architect said that if Farnsworth paid the $4,500 tab then he’d waive any professional fee and consider the matter closed. Her camp said that she’d be “willing to settle” for $1,500. They were too far apart to come to a settlement. Wiley put Mies through to Sonnenschien Berkson Lautmann Levinson & Morse. I’ll just call them SBL from here on out. They pushed him to sue.

This would’’t be your typical court case. The plaintiff and defendant would lay their cases out to a Special Master. This person would then submit a report to a judge that detailed recommendations in regard to how it should be ruled.

Bohrer would continue to represent his client through this case. SBL, meanwhile, handed the case to litigator John Fassler. He argued that Mies was owed about $3,500 for unpaid out-of-pocket labor costs as well as an additional $16,600 for his architectural and general contracting services. Even though Mies and Farnsworth had never formally discussed the latter fee, Faisler argued that they had a contract “partly expressed and partly implied.”

Bohrer laid out a countersuit. He claimed that Mies had mishandled the construction of the house. He argued that it could have been built at that original $40,000 price point, but the architect was more focused on creating his next masterpiece than designing a house. The unusual construction methods and lavish materials sent construction costs into the stratosphere. What’s more, he said that Mies intentionally kept the rising cost of the project away from his client. Bohrer sought $35,000, which roughly split the difference between the $40,000 quote and what she’d already spent on the home.

Faissler focused on brushing off those negligence claims. William Goodman was an engineer that Mies went to occasionally for mechanical design. He testified that there were no major flaws in the design of the home and that the architect had given the project the proper attention.

Farnsworth had also been more involved in the project than the defense led Nelson to believe. There were numerous meetings concerning the materials, layout, and costs. Furthermore, the firm had made at least some efforts to reduce the cost of the house and delay construction until the funds were sorted. Mies reduced its size by 10 percent sometime in 1949. She knew about this and even asked him to assure her that it wouldn’t compromise the design. Photographs of Dr. Farnsworth in the studio cast further doubt on these accusations. Communication was definitely an issue, but not to the extent that the defense claimed.

Initial hearings began on May 23, 1952, and went on until July 3rd. Final oral arguments, meanwhile, weren’t made until July 30th, 1953. Special Master Nelson didn’t get around to submitting the report to Judge Harry C. Daniels until the May of the following year. It took the side of Faissler on many points and concluded that Mies was entitled to nearly $13,000 plus “the cost of this proceeding.” This number was a calculation that effectively awarded Mies his unpaid out-of-pocket costs and a “reasonable” professional fee.

Both lawyers followed up on the report, but Nelson soon dismissed all of Bohrer’s objections. This was not the end of the case. It would be dragged out for a few more years. Judge Daniels sat on the case for two years without issuing a final ruling. It was then passed down to another judge, who wanted the two parties to come to some kind of settlement. Two weeks of negotiations followed, but neither one of them wanted to give any ground.

Mies eventually cracked. The suit wore him down and he wanted nothing more than to be done with it. He confided with David Levinson, a senior partner at SBL, and told him that he’d be willing to settle for nothing “if she would just stop slandering us.” Levinson, ever the litigator, pointed to the favorable Master’s report and said Mies had to get something out of the case.

Bohrer was on vacation, so Faissler’s team spoke with his son Mason. Faissler suggested $2,500, which was between the Master’s original award and the cost of an appeal. This also nearly split the difference between the Mies's original request of $4,500 and Farnsworth’s counter to “settle” for $1,500. Farnsworth accepted, and the two of them were out of each other’s lives for good.

LATER YEARS

Dr. Farnsworth didn’t let the drawn-out legal battle color her experience with the home. She enjoyed it for about 20 years, and she could’ve had many more years from it if it weren’t for some developments in the area. The county planned on replacing the Fox River bridge with a new one that would be much closer to her home. Dr. Farnsworth didn’t want this plan to go through, as it would have made her house visible to the road and house.

She tried a few things to get the county to change its mind. First, she tried to have two acres of the property turned over to the state after Native American artifacts were found near the house. She submitted the bid to the Illinois Department of Conservation, but they never got back to her. She then said she’d turn the property over as a park if the bridge was called off. The county turned the proposal down. For her final argument, she said that the house and land were an important work and that the bridge would disrupt it. Dr. Farnsworth wanted $250,000 in damages for the acreage that would be taken away from her but ultimately settled for $17,000.

She took this as the sign to finally let go of the house. She put it up for sale in the classified section of the Chicago Tribune and hoped that someone with ample amounts of money and patience would take it off of her hands.

Now let’s pivot for just a moment. In 1967, real estate developer Peter Palumbo commissioned Mies van der Rohe to take on the Mansion House Project in London. While this project was underway, he visited Mies’s grandson Dirk Loan in Chicago and asked if the architect would have any interest in building a house for him in Scotland. Lohan thought that, if Palumbo wanted a Mies-designed residence so badly, then he could forego the construction process and buy Farnsworth House outright. He got in touch with Edith and purchased the house for $120,000. They made the deal in 1968, but the two of them agreed that she’d stay in the house until 1971. When the time finally came, she moved to Italy and pursued poetry. She remained here until her passing in 1977.

Palumbo, like Farnsworth, used the house as an occasional getaway. His primary residence was in London, so it would have been unfeasible for him to maintain the property on his own. As a result, he hired a full-time caretaker to look over the house while he was away. He made a few changes to the property while it was under his ownership. The old furniture was done away with and replaced with the Mies-designed pieces it was originally conceived with. The addition of air conditioning went a long way to make it more bearable during the summer months. Dirk Lohan created several pieces of his own for the home and modified the fireplace to mitigate the flying ash issue.

Palumbo didn’t have to fight with Mies for creative control or defend himself in court, but his time owning the home wasn’t without its headaches. It experienced a catastrophic flood in July of 1996 when the area got 18 inches of rain in a 24-hour period. Two glass panels gave way to the rushing waves, letting nearly 5 feet of water into the interior. The service core was critically damaged and many pieces of furniture were lost forever. Some eyewitness accounts even say that an Andy Warhol could be seen floating downriver. It cost about $500,000 to get it back in order.

Palumbo’s declining health motivated him to move on from the property around the turn of the millennium. Instead of pursuing a private sale, he decided to auction the house off through Sotheby’s. This sent Chicago representatives and architectural enthusiasts into a frenzy. There was a possibility that someone could buy the house and move it to another state. There were rumblings that some potential buyers wanted to relocate it to Pennsylvania or Wisconsin. One party even wanted to build a subdivision on the land.

Fortunately, a collective of preservationists was able to purchase the home for $7.5 million. The funds were pooled together by the National Trust, the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois, and over 350 donors. Some of them were only able to pitch in a few dollars. Others contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cause. A New York Times article from December 2003 says that 30 people gave over $250,000. One person came in at the last moment and offered to give that amount as well. By the time the phone call was over he ended up pledging three times that amount.

Edith Farnsworth House was opened to the public in 2004 and over 10,000 guests visit it annually. Guided tours are performed throughout most of the year and exhibitions explore the wider history and impact of the home. Presentations on Peter Palumbo, Mies van der Rohe, and Roger Brown are going on through the end of 2023.

Keeping the home in good condition has been more difficult than ever. The steel used throughout the property rusts and corrodes. Many of the glass panes have been replaced as well. Only five of the 17 original windows remain. National Trust and the Preservation Council have replaced 4 panes and replaced 6 windows since acquiring the property in 2003.

The most serious threat to the house has been, without a doubt, the increase in floods in the area. There was at least one serious event while it was under Edith’s ownership. It flooded in 1954, and she had to make a daring escape on a paddleboat with her violin and poodle in tow. Incidents like this have only increased in the last 30 years. It flooded a mere year after the ruinous event in 1996. The subsequent renovations rang up for $250,000. The most recent serious event happened in 2008 when weather conditions from Tropical Storm Lowell and Hurricane Ike put the floor under 18 inches of water. An article from Art21 Magazine notes that while some fixed wood panels were damaged, the movable furniture was saved because it was all placed on top of milk crates.

With the onset of increased urbanization and climate change, these incidents will, unfortunately, become more common in the future. It might seem like a fool’s errand to save the home in the face of conditions like these, but there just might be a solution on the horizon. The National Trust began working with the architectural firm Robert Silman Associates on the issue. They presented the Trust with a variety of options. RSA proposed everything from permanently elevating the house up to moving it to another location entirely. Other, more bizarre solutions included a complex barrier system and a strange buoyancy system that would literally see the home float in the event of a flood. None of the aforementioned ideas appealed to them. As they were either unrealistic or too far removed from Mies’s original vision.

They settled on a hydraulic-based system that could raise the house temporarily during a flood. It appealed to the Trust because the core experience would remain intact. They wouldn’t have to relocate it elsewhere on the lot or install some intrusive mechanism. Visitors would be none the wiser. In this plan, the house would be relocated temporarily while the new system is installed. The lower terrace would also be essentially severed from the rest of the structure. The upper portion would be raised from its original position by up to 8 feet when the floodwaters come rushing in.

A 2020 article from Architects.org quotes Ben Rosenberg, a principal engineer at RSA. He said, “the house will take between 30 and 90 minutes to raise, depending on the final design.” This would be more than enough time for them to react to floods, which Rosenberg says can be anticipated days in advance. It’s a fascinating solution, though I’m only giving a general overview of it. Robert Silman provided a more in-depth explanation at a Chicago conference in 2014. I’ll link it in the description if you’d like a deeper understanding. It is also a long way out from actually being implemented. The system is part of a larger $10 million renovation plan that is intended to return the home back to its former glory.

We can only hope that Edith Farnsworth House endures so that it can inspire generations to come.